The Real Lord of the Flies

Now that we know dystopia is not inevitable, can we investigate why we’ve come to believe that it is?

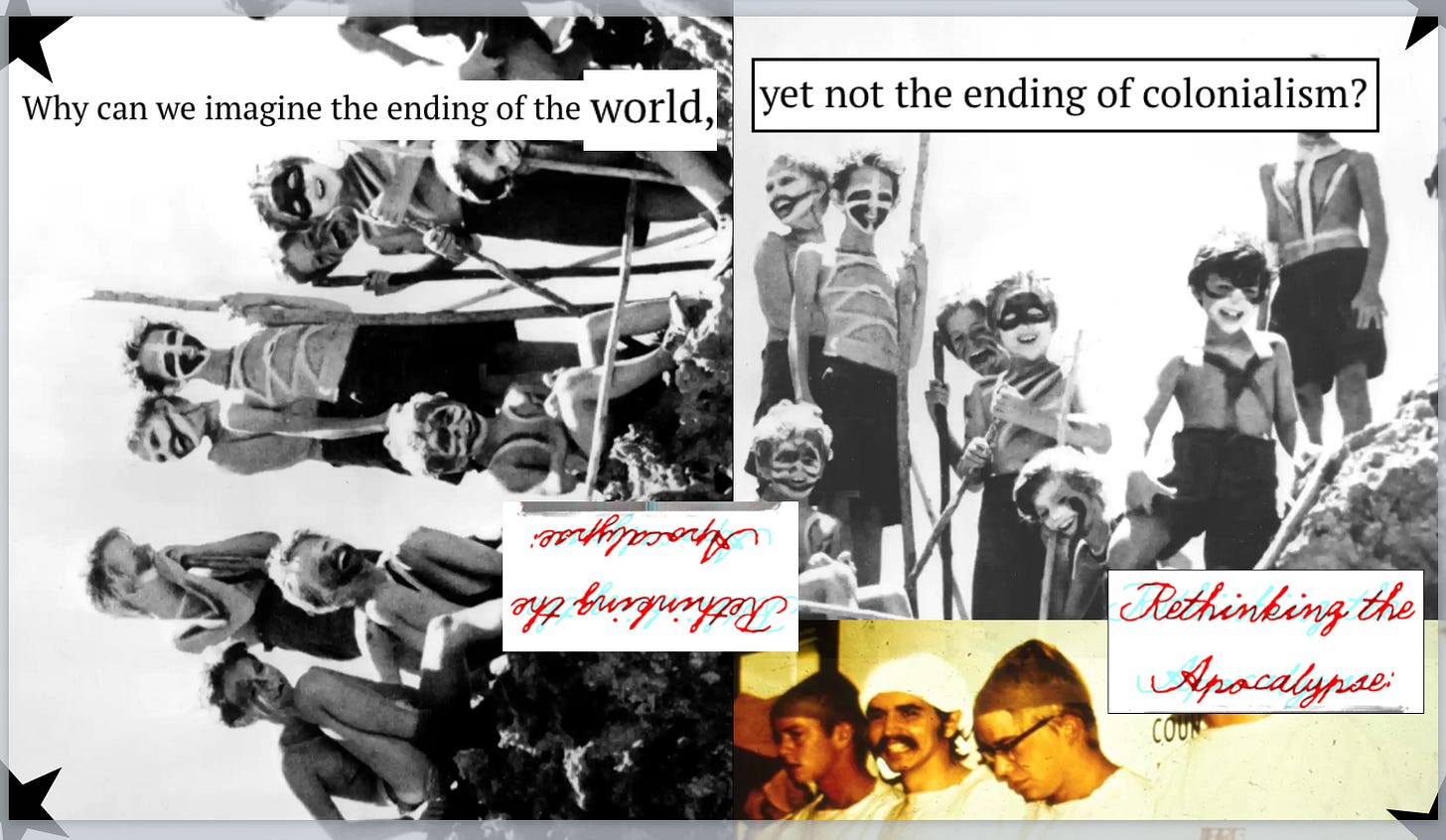

A decade after British author William Golding published the now-classic piece of literature, Lord of the Flies, six Tongan boys, bored of the food at school, “borrowed” a fishing boat and took it out to sea for an adventure.

To make a long story short: the boys fell asleep, got caught in a storm, lost their rudder and sail in the wind and waves, drifted for eight days without food and only a little rainwater, and then shipwrecked on a rocky islet in the Pacific Ocean where they would end up marooned for 15 months.

Rutger Bregman: The real Lord of the Flies: what happened when six boys were shipwrecked for 15 months (The Guardian, 9 May 2020)

The Tongan boys had a very different experience from the characters in William Golding’s book. They spent those 15 months taking care of each other—without devolving into conflict, madness, or cannibalism—until one day a sailor happened upon the rocky islet and rescued them.

During their time on the islet (which, by the way, is currently deemed “uninhabitable”), the boys built a small commune that included a food garden, a rainwater catchment system, a gymnasium and badminton court, chicken pens, and a permanent fire.

While their story has been lost to obscurity, William Golding’s version remains, serving as the inspiration for Survivor, shows like Yellowjackets, and the common belief that humans in difficult situations will always turn on each other.

Why do we continue to uplift and reference William Golding’s story while allowing the real life (non-conflict driven) version to fall by the way side?

William Golding was known for “half-joking” that he would have been a Nazi had he been born in Hilter’s Germany and making statements like, “I have always understood the Nazis because I am of that sort by nature.”

I don’t know about you, but that makes me question the themes and messages in his literature. I’m not saying that we should judge him or not read his work. What I’m asking is that we consider them with a more critical lens. I believe it is fair to say that Lord of the Flies and its depiction of conflict has shaped our culture and our societal beliefs around human behaviour and the human spirit.

And, yes, history has proven that the human spirit does contain horrific multitudes. But that is just one lens, one perspective, and one angle on the human spirit. I do not believe that it should not be the lens we place upon humanity as a whole. I think you would agree.

I think you would also agree that our culture is overrun with stories like Golding’s Lord of the Flies and very, very thin on stories that depict humanity as practiced by those Tongan boys.

Why is that?

Another cultural touchstone of human behaviour is the Stanford Prison Experiment. Conducted in 1971 at Stanford University, the prisoner and guard simulation has become one of the most famous psychological studies of all time.

In “The Lifespan of a Lie,” Ben Blum writes,

Whether you learned about Philip Zimbardo’s famous “Stanford Prison Experiment” in an introductory psych class or just absorbed it from the cultural ether, you’ve probably heard the basic story.

Zimbardo, a young Stanford psychology professor, built a mock jail in the basement of Jordan Hall and stocked it with nine “prisoners,” and nine “guards,” all male, college-age respondents to a newspaper ad who were assigned their roles at random and paid a generous daily wage to participate. The senior prison “staff” consisted of Zimbardo himself and a handful of his students.

The study was supposed to last for two weeks, but after Zimbardo’s girlfriend stopped by six days in and witnessed the conditions in the “Stanford County Jail,” she convinced him to shut it down. Since then, the tale of guards run amok and terrified prisoners breaking down one by one has become world-famous, a cultural touchstone that’s been the subject of books, documentaries, and feature films — even an episode of Veronica Mars.

The Stanford Prison Experiment has seeped into the cultural consciousness, just like Lord of the Flies, as proof that humans (or at least men and boys) will always turn on each other—that, given the right circumstances, we will always devolve to an us versus them scenario that often includes horrific violence.

But the Stanford Prison Experiment, just like Lord of the Flies, was a work of fiction.

In April 2018, French academic and filmmaker Thibault Le Texier published Histoire d’un Mensonge [History of a Lie], based on newly-released documents from Zimbardo’s archives at Stanford University that told a dramatically different story than that of the experiment.

Transcripts between Zimbardo and his staff revealed that they manipulated the experiment. In a 2018 study entitled Rethinking the nature of cruelty: The role of identity leadership in the Stanford Prison Experiment, researchers concluded that—

The totality of evidence indicates that far from slipping naturally into their assigned roles, some Guards actively resisted and were consequently subjected to intense efforts from the Experimenters to persuade them to conform to group norms for the purpose of achieving a shared and admirable group goal.

Zimbardo also lied about the parameters of the experiment. Participants entered the study under the impression that they could leave at their own will, but when they requested to be let out, Zimbardo wouldn’t let them go.

This led prisoners like Douglas Korpi to breakdown by screaming, kicking at the door, and demanding to leave. Korpi, now a forensic psychologist, explained years later that his fear of failing his exams (he thought he would have time during the experiment to study) that led him to fake the freakout.

It was breakdowns like his that forced the early cancellation of the experiment and led to the “scientific” evidence that any person could turn into a corrupt prison guard given the right circumstances.

In the wake of World World II, this belief was popular at the time. Leading up to the Stanford Prison Experiment, as Maria Konnikova reported in the New Yorker in 2015, research had been growing that “ordinary people, if encouraged by an authority figure, were willing to [harm] their fellow-citizens.”

So after Zimbardo’s experiment, the belief that “regular people, if given too much power, could transform into ruthless oppressors” became status quo belief.

It wasn’t until decades later that new evidence emerged questioning the validity of the experiment and the bias behind the research—research that made its way as truth into every psychology textbook in the Western world.

I've been thinking about dystopia vs. utopia a lot lately. The thing is, I think we DO have stories of human cooperation under stress in the media (i.e. The Wilds vs. Yellowjackets), but those articles, stories, shows, etc. are less successful. But I don't know if that's because people are less interested, or there is less marketing, or because the news media is less interested in headlines about human good, etc.